Long before FBI computer contractor and Clinton operative Rodney L. Joffe allegedly trolled Internet traffic for dirt on President Trump, he mined direct-marketing contact lists for the names and addresses of unwitting Americans to target in a promotional scam involving a grandfather clock.

Not just any clock, mind you, but a “world-famous Bentley IX” model, according to postcards his companies mailed out to millions of people in the late 1980s claiming they’d won the clock in a contest they never entered. There was just one hitch: the lucky winners had to send $69.19 in shipping fees to redeem their supposedly five-foot mahogany prize.

Tens of thousands of folks forked over the fees, only to discover the grandfather clock that arrived was nothing as advertised. It was really just a table-top version made of particle board and plastic and worth less than $10. Some assembly was required.

The scheme generated thousands of complaints, sparking federal and state investigations. Joffe and his then-California partner, Linda M. Carella, were eyed by federal postal authorities and several state attorneys general for allegedly operating a multi-state mail-order scheme. Joffe settled several state lawsuits by agreeing to refund hundreds of thousands of dollars mainly to elderly victims, according to several published reports at the time.

Joffe and his attorney did not respond to requests for comment. But in a phone interview, Carella said that Joffe ran the operation. “I was just the secretary, the receptionist,” Carella, 76, said from her home in Florida, where she is now retired. She did say she picked up the returned postcards and checks from mailboxes.

Carella said she quit after the investigation: “I said I don’t want anything more to do with this . . . I have not seen Rodney since then.”

But Joffe pressed on with his direct-mail marketing business before packing up for Arizona a few years later. Federal and state tax lien records reveal Joffe — who also sent out mailers for skincare and other beauty products — owed more than $110,000 in back taxes on his property in Los Angeles in 1995.

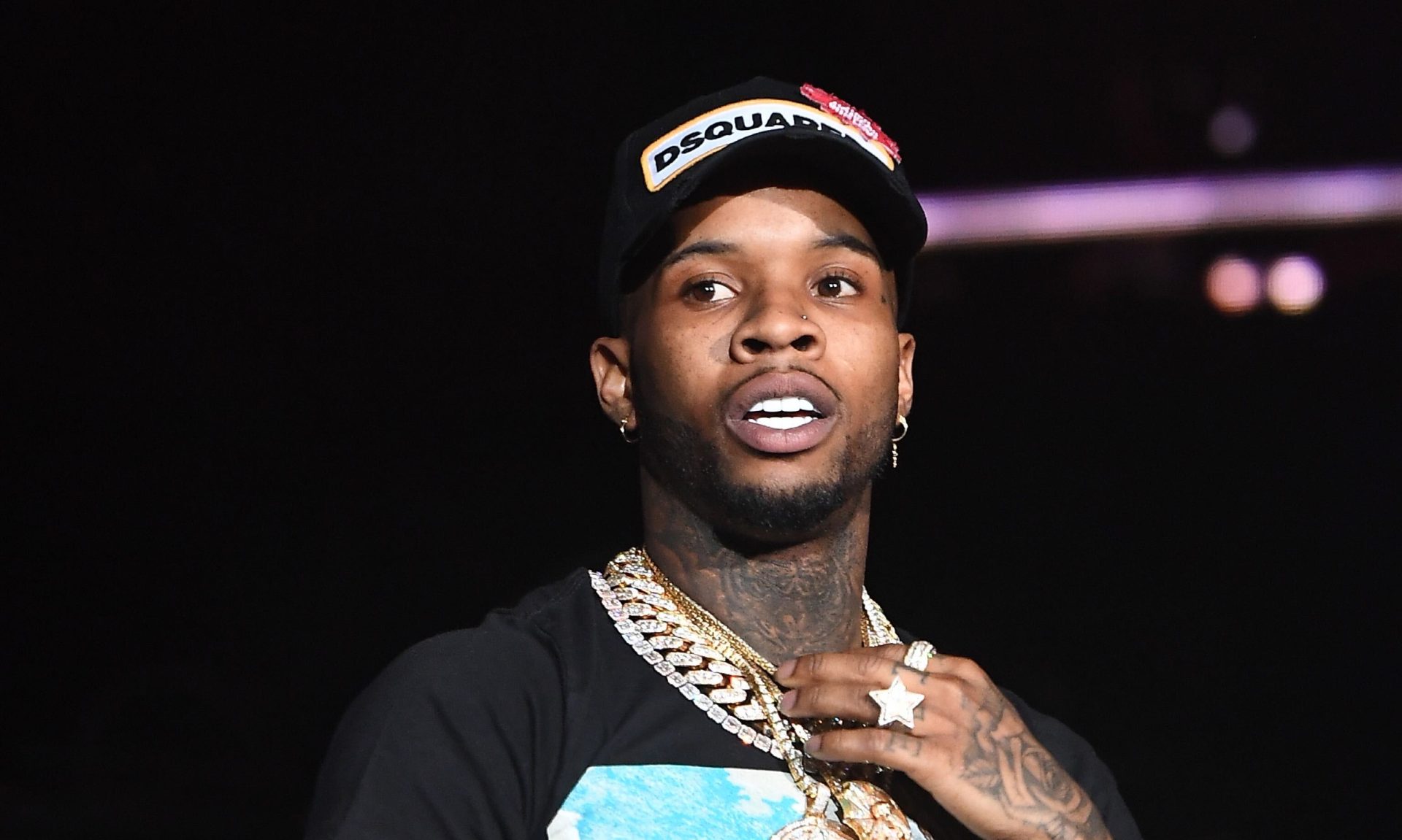

Joffe’s checkered past now has national security ramifications after the South African-born computer expert was outed as a key player in Special Counsel John Durham’s ongoing Russiagate probe.

To date, he has not been charged with a crime. But in a September indictment of former Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann, and a court filing last week, Durham has suggested that Joffe (identified as “Tech Executive-1”) was at the center of an effort to monitor President Trump’s communications and then share the information with Clinton associates.

Former prosecutor and assistant FBI director Chris Swecker said the credibility issues that cropped up from Joffe’s early career raise questions about how he managed to pass an FBI personal background check and obtain the government’s highest security clearances, although he noted that such background checks were often ridiculed in the bureau as “a joke.” In addition, the federal mail-order probe involving Joffe’s companies might not have raised serious red flags since the case was opened decades earlier and was settled without any charges or judgments against Joffe.

Another part of the answer as to why Joffe’s past remained buried may involve how successfully he appears to have reinvented himself during the 1990s.

He relocated then to Phoenix from Los Angeles and changed the name of his mass-marketing firm American Computer Group to “Whitehat Data Services.” Instead of targeting consumers, he developed a reputation as a cyber-security expert and, ironically, a champion of consumers battling abusive direct-marketers and spammers.

Perhaps it was a sign of his redemption. But Joffe soon joined the board of PlasmaNet Inc., a marketing network that until recently operated FreeLotto.com, an online sweepstakes game. PlasmaNet has had to pay millions of dollars in fines for deceptive advertising. Echoing the grandfather clock scam, PlasmaNet led consumers to believe they won free prizes when in fact they had to pay $14.99 a month to claim them. RCI has learned that FreeLotto.com was a customer of UltraDNS, an Internet resolution company founded by Joffe. Business incorporation records show Joffe remains a PlasmaNet director.

A decade later, Joffe moved to Washington, where he eventually landed lucrative security-related contracts with the FBI and Pentagon requiring top-secret clearance.

In 2006, Joffe joined Neustar Inc., a Beltway computer contractor that, among other things, secures and maintains Internet servers for federal agencies, including the White House. This high-level position gave the alleged former grandfather clock wheedler access to a proprietary archive of Internet traffic records — both public and nonpublic— known as “DNS logs.”

These logs reveal the back-and-forth pinging that computers and cellphones generate when they communicate with Internet servers, including ones transmitting emails.

It also put him in the same orbit with political VIPs. Joffe started advising not only FBI brass but White House officials on cybersecurity matters. By 2016, his access to proprietary internet logs became of interest to operatives for the Hillary Clinton campaign, who appear to have offered him a job in a Clinton presidency. (Shortly after Clinton’s loss to Trump in November 2016, Joffe said in an email: “I was tentatively offered the top [cybersecurity] job by the Democrats when it looked like they’d win. I definitely would not take the job under Trump.”)

One of those operatives was ex-Clinton attorney Sussmann, indicted by Durham last fall in connection with allegations of lying about his work on the project for the campaign.

In the indictment and recent court filings that widen the case, Durham accused Joffe of exploiting Neustar’s nonpublic data to monitor Trump’s Internet activities even after the 2016 election — through early 2017. He shared the sensitive information with Sussmann.

The prosecutor said Joffe mined data from Trump Tower, Trump’s Central Park West apartment building and even the Executive Office of the President “for the purpose of gathering derogatory information about Donald Trump.”

According to court papers, Joffe cherry-picked data to create a “narrative” that Trump was secretly communicating with the Kremlin as part of the Clinton campaign’s effort to make the GOP nominee look like he was compromised by Russia, a foreign adversary.

Joffe led a team of computer researchers trying to link Trump to Russian Alfa Bank through private DNS logs. He handed off their findings to Sussmann who fed the data to the FBI to drive an investigation and bad press against Trump.

“The data was highly manipulated,” said Robert Graham of Atlanta-based Errata Security, an independent cyberforensics expert who examined the logs and debunked the link at the time. He suspects Joffe and his biased crew set out to invent a connection between Trump and Russia.

“A link between Trump and Alfa bank wasn’t something they accidentally found, it was one of the many thousands of links they looked for,” he added. “The purpose was to smear Trump.”

Though Graham as a Clinton supporter shares Joffe’s disdain for Trump, he said the suspicious server data were easily explained as innocent spam traffic. Graham noted that Trump didn’t even have control over the domain in question: trump-email.com. It was created by a hotel marketing firm that inserted Trump’s name in the domain.

“Hints of a Trump-Alfa connection have always been the dishonesty of those who collected the data,” Graham said.

Even though Joffe encouraged Sussmann to present the server data to the FBI as possible evidence of foreign espionage, he privately confessed to his researchers in an August 2016 email obtained by Durham that the host for the trump-email.com domain “is a legitimate valid [marketing] company” — Boca Raton, Fla.-based Cendyn.

“We can ignore it,” Joffe said, “together with others that seem to be part of the marketing world.” He urged his team to keep searching for data that would “give the base of a very useful narrative.”

In previous statements, lawyers for Joffe and the researchers he recruited have said they had no political ax to grind but were monitoring Trump to track a credible national security threat related to Russia. But Joffe’s lead researcher — Manos Antonakakis of the Georgia Institute of Technology — revealed in one email obtained by Durham that “the only thing that drives us is that we just don’t like [Trump].”

In a public statement, a spokesman for Joffe argued that the then-Neustar executive had authority to mine the White House data: “Under the terms of the contract, the data could be accessed to identify and analyze any security breaches or threats,” including concerns about Russian interference in the election.

Joffe’s second-act success in government seems rooted in a simple fact: “He has friends in high places,” proferred a career Justice Department official.

Secret Service entrance logs reveal Joffe visited the White House several times during the Obama administration. And in 2013, Comey gave Joffe an award recognizing his work helping agents investigate a cybersecurity case. Sources said that Joffe has also worked as an FBI informant on various cybersecurity cases opened by the bureau over roughly the past 15 years.

Sussmann’s attorneys have pointed to that acclaim to explain why Sussmann trusted the findings from Joffe he shared with the FBI.

“Far from being a stranger to the FBI, [Joffe] was someone with whom the FBI had a long-standing professional relationship of trust and who was one of the world’s leading experts regarding the kinds of information that Mr. Sussmann provided to the FBI,” Sussmann’s lead defense lawyer Sean Berkowitz of Latham & Watkins said in a court filing last year.

A recent court paper filed by Durham in the Sussmann case suggests he may be looking into Joffe’s relationship with the FBI. The document, which discloses information to Sussmann’s lawyers as part of the discovery process, reveals that a criminal grand jury in D.C. has obtained “approximately 226 emails from within the FBI’s holding involving a company founded by [Joffe].”

Durham said that his investigators are “also conducting other searches and communicating with other government agencies regarding [Joffe’s] companies.”

The 67-year-old Joffe is commonly described as an award-winning and highly respected computer expert. But colleagues say he is more of an operator.

Graham said he’s “a quite average” computer programmer and network analyst. “He’s more of an executive than an operations guy.”

In a 2015 promotional video by Neustar, Joffe disclosed that his real gift is recruiting other experts, making phone calls to people in high places, and providing the resources needed for projects.

“I’m not the smart guy in the room. I’m really the dumb guy that carries the bags — but fortunately in those bags, I have a lot of money,” Joffe said with a grin. “So my role has really been carrying the bags of money to help whenever I can when folks in the [cyber-security] community want things. I’m really happy to be able to do that kind of thing.”

“So those are the things I really do,” he added. “I’m not really good at actually understanding spam and finding that. I’m not any of those things. I couldn’t have an intelligent conversation about the techniques and methods used.”

Reprinted with permission from RealClearInvestigations.