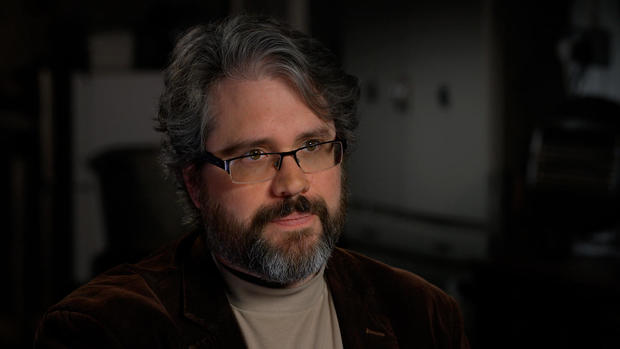

The war crimes in Ukraine are among the worst of the 21st century, but they are just the latest in a history of assassinations and mass murder at the hands of Russian President Vladimir Putin. We know this, in large part, thanks to a team of online data detectives that calls itself Bellingcat. Since 2014, Bellingcat investigations have exposed Russia’s undercover hit squads and tied Russian troops to atrocities. Suffice to say the Russian government denies everything you are about to see in this story. But that’s exactly where Bellingcat comes in. Bellingcat’s founder, Eliot Higgins, has created a method of mining online data and social media to put the lie to disinformation and unmask Vladimir Putin.

Eliot Higgins: I feel it’s almost my duty that when we’re faced with all this information showing terrible things that are happening, it’s to put it out there. It does involve risk. But then defending liberty, human rights, democracy involves taking risks. It’s when we stop taking risks and we let the fear take hold that we see democracy die.

We met Eliot Higgins last month in London as Bellingcat was building a database of social media exposing apparent war crimes in Ukraine. Eyewitness accounts of attacks on neighborhoods, assaults on hospitals, and murders of civilians are being collected and published on Bellingcat’s website for all to see.

Nearly everyone in Ukraine is a witness with a camera. Bellingcat is combining tens of thousands of social media posts to make them searchable by place and time.

Eliot Higgins: And we look [at] as many sources as possible and use those sources to build a picture of what happened. Videos, photographs, satellite imagery. Then we look at the witness statements and the various allegations made by either side.

Locations and times are corroborated with independent sources including satellite images and Google Street View. The goal is to provide verified evidence for future criminal trials.

Eliot Higgins: And it also means that we’re collecting an archive of material that for future generations, they can go back and look at this material. I mean, it’s often said that, you know, history is written by the victors. But it’s being written now. And it’s being preserved now.

Ukraine is the biggest project in Bellingcat’s short career. Higgins started Bellingcat in 2014 as, sort of, an accidental activist.

Eliot Higgins: I was not someone with a professional background. I was doing this merely as a hobby.

Scott Pelley: What were you doing for a living at the time?

Eliot Higgins: I was working for a company that housed refugees in the U.K. I then worked for a company that manufactured pipes. And then a company that manufactured lingerie. So, I had a wide range of experience but nothing that was directly related to conflict.

On his off-hours, the conflict in Syria fascinated him—especially how social media was exposing atrocities there.

Scott Pelley: You found your calling.

Eliot Higgins: Indeed I did.

But his search for the truth began with a fairytale.

Scott Pelley: Where does the name come from?

Eliot Higgins: So, Bellingcat comes from the name of a fable, Belling the Cat. And it’s about a group of mice who are very scared of a very large cat. So, they have a meeting, and they decide to put a bell on the cat’s neck. But then they realize that no one knows how to do it, and no one is willing to volunteer to do it. So, what we’re teaching people to do is bell the cat.

Higgins belled his first predator in 2014 when Russia went to war in eastern Ukraine. Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 was high over Ukraine on its way to Asia when a missile brought it down. 298 were killed. Everyone denied responsibility. But Higgins noticed, in the hours before the shootdown, there were many social media posts from bystanders who saw a missile launcher on a flatbed trailer traveling in eastern Ukraine.

Eliot Higgins: We started discovering social media posts of people who had seen the missile launcher being transported. And we also had social media posts from people who said there’s a rocket that’s just been shot up from this direction. And we could actually use their social media profiles to figure out where they lived.

Other posts were written by Russian soldiers homesick for family. Higgins found clues in each image—billboards, buildings, road signs—that let him fix the location and time of each post. When he arranged all of the social media into a timeline, he could run the convoy backward to its starting point.

Eliot Higgins: Using all those videos we were able to trace it all the way back to the military brigade it came from, the 53rd Air Defense Brigade.

Scott Pelley: In Russia.

Eliot Higgins: In Russia. And we used their social media profiles, the soldiers, their family members and everyone around them to reconstruct basically their network online which meant we could get their names, their ranks, their photographs, see who was in that convoy and who traveled to the border. So that allowed us to prove that Russia provided the missile launcher that shot down MH-17.

Bellingcat published its findings and Russia imposed a new law.

Christo Grozev: The Russian government passed a specific law banning soldiers from carrying– mobile devices during hostilities, which is dubbed in Russia “the Bellingcat law.”

Christo Grozev, is executive director of Bellingcat, leading its 30 full-time researchers. His personal focus has been on Russian political assassinations.

Scott Pelley: What have you learned about how Vladimir Putin operates?

Christo Grozev: What we have found out is that none of these crimes could have been perpetrated without Vladimir Putin being– in the know, and not only aware but approving of all of these crimes. So, in a nutshell, what we found out was that Putin is operating an industrial-scale assassination program on his own people.

Bellingcat’s next big project, the Russian assassination program, started in 2018 after a Russian defector and his daughter, living in Britain, were poisoned with a military-grade nerve agent. The British had passport photos and false names of two suspects but nothing else. Grozev knew that Russia’s government and commercial records are for sale on an online black market. So, with the fake names, he bought the suspect’s passport records.

Scott Pelley: The passport numbers on the two passports were identical, except for the last digit?

Christo Grozev: The last digit, exactly.

Scott Pelley: So they were clearly made one after the other?

Christo Grozev: Exactly.

Suspicious, Christo Grozev started data mining. Based on official records, it seemed as though both men were born at the age of 32. And there was an unusual stamp on the passport documents.

Christo Grozev: There was a big black stamp in the corner of their file which said, “Do not provide information on this person. In case of a query, call this number.” And sure enough, we called that number, and it was the Ministry of Defense.

When the Ministry of Defense answered, Grozev knew the would-be assassins were military intelligence agents. To match their faces to their true identities, he spent weeks combing yearbooks and photographs from Russian military academies.

Christo Grozev: The end result was that we were able not only to identify the real identities and the affiliation to the military intelligence, we were able to find a third and a fourth member of the same kill team that the British did not even know about.

Over months, Grozev uncovered a network of Russian hitmen, working throughout Europe, armed with nerve agent from a government lab. He bought airline manifests and found some of the assassins’ travel overlapped the campaign stops of alexei navalny, the top political opponent of Vladimir Putin.

Christo Grozev: And we found a total of 66 overlaps, way beyond any statistical possibility for a coincidence.

Scott Pelley: They’d been shadowing him for months, years?

Christo Grozev: They’d been shadowing him for four years. They started shadowing him the moment he announced his presidential aspirations in 2017. Apparently being on standby for a possible assassination whenever they would get the signal.

A signal came in 2020. On a campaign trip, Navalny was poisoned with that same nerve agent. He recovered in a German hospital, returned to oppose Putin, and is now in prison. Bellingcat’s investigation found assassins also tailed other Putin opponents.

Christo Grozev: And we found, for example, that the team that had poisoned Navalny had tailed at a minimum 12 other opposition figures, three of whom had been killed, in fact, poisoned.

Investigations like that are published on Bellingcat’s website which is blocked in Russia. Bellingcat is a nonprofit foundation which has trained more than 4,000 journalists and war crime investigators in its techniques of geolocation, verification, and data mining.

Alexa Koenig: We’re headed into an entirely new era of human rights investigations, and war crimes investigations, more generally.

Bellingcat trained Alexa Koenig’s team at the University of California, Berkeley, Human Rights Center. Koenig is the executive director of the center which has used Bellingcat’s techniques to expose atrocities in Myanmar and chemical attacks in Syria.

Alexa Koenig: They’re showing the world that you don’t have to be a large outfit like The New York Times or the International Criminal Court to pull these disparate bits of information together, and actually get underneath who’s done what to whom and when.

Still, Koenig says, this new era is challenged by the fact that anyone with an internet connection can be an investigator.

Scott Pelley: The problem becomes how do you make sure they’re right?

Alexa Koenig: That’s always the risk. And I think one big concern in this space is the ethics of doing this work and making sure that you don’t get it wrong.

Alexa Koenig’s UC Berkeley center recently worked with the United Nations to publish guidelines for witnesses who post evidence and for amateur investigators.

Scott Pelley: Standards.

Alexa Koenig: Yes.

Scott Pelley: Rules of evidence.

Alexa Koenig: Exactly. So a lotta people are being really innovative and creative about how to use a lot of digital tools and techniques to ultimately solve these puzzles. But the problem is a lot of them are not trained as legal investigators. They’re not thinking about things like chain of custody, and how do you establish that something you grabbed from the internet hasn’t been changed in transit, and should actually be trusted as reliable once it reaches a court of law? So, our work is hopefully designed around helping them do that in a way that maximizes that value for accountability.

Scott Pelley: Ultimately, what is your hope for your Ukraine investigations?

Christo Grozev: We already have been approached by the International Criminal Court. We’ve been approached by several prosecution authorities in Europe, who want to initiate their own cases– into war crimes. And we not only hope, but we know that our database, our search now will be used in a future let’s call it something like a Nuremberg trial.

There may be no accountability for Russia in a courtroom, but the work of traditional journalists and Bellingcat’s expanding database are overwhelming Putin’s propaganda.

Scott Pelley: You have exposed a number of Russian intelligence operations, some of which involve assassins. And I wonder if you fear for your own safety.

Eliot Higgins: You have to be careful about your own security. It’s an extra level of paranoia. It doesn’t kind of rule my life. But you just have to be kind of hypersensitive sometimes to certain things.

Scott Pelley: Why take the risk? Why you?

Eliot Higgins: If Russia is to sustain itself, it has to rule by fear. You can’t just let that fear overtake you. If you’re in a position to do something, if you have information, if you have the motivation and you have the strength to do it, you should do it.

Ukraine will be the most thoroughly documented war in history. Russia says no civilians have been harmed by its forces and scenes of atrocities are staged. But Putin’s defense is a throwback to a previous century. Analog denials in the age of the digital witness.

Produced by Henry Schuster. Associate producer, Sarah Turcotte. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Michael Mongulla.